Look at the data!

We give a lot of lip service to "the science" and "the data", but it's often not that straightforward. We all know "the data" can be misrepresented or sliced in a hundred different ways to support a hundred different agendas. Often, it's these agendas that set policy and data is used to backfill the position. This is a fault of the policymakers, not the data or even necessarily "the scientists".

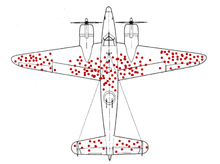

My favorite example of this is the canonical example of Survivorship bias.

The story involves British bombers getting shot down during WWII, after which a careful inspector diligently noted the location of every bullet hole.

Obviously, the team concluded, we should add heavy armor to the places where the planes get shot.

Fortunately, before they spent millions on ineffective armor, a mathematician pointed out that, since the planes weren't shot down, they were armoring the wrong parts of the plane.

He pointed out that the bullet holes on the planes that returned indicate strong spots that don't need additional armor.

Instead, he suggested, armor the parts of the plane that haven't been shot, because, had they been shot there, they wouldn't have made it back.

Interpreting evidence can be difficult, even for the experts who are trying their best.

Obviously, the team concluded, we should add heavy armor to the places where the planes get shot.

Fortunately, before they spent millions on ineffective armor, a mathematician pointed out that, since the planes weren't shot down, they were armoring the wrong parts of the plane.

He pointed out that the bullet holes on the planes that returned indicate strong spots that don't need additional armor.

Instead, he suggested, armor the parts of the plane that haven't been shot, because, had they been shot there, they wouldn't have made it back.

Interpreting evidence can be difficult, even for the experts who are trying their best.

Nevertheless, a complicated subject like medicine often needs distilled down to bullet points, even for physicians. In simplifying treatment decisions, some resolution is inherently lost. The 80/20 rule says this is probably good enough for most cases. The answer, it is often said, is "it depends"; "guidelines are just guidelines" comes from this, too.

If you are trained in basic first aid - usually, between 8 and 24 hours - the treatment protocols/guidelines you learned didn't offer much room for flexibility. Words like "never" and "always" are thrown around to impress points upon students. Often, first aid instructors don't have the medical background to comment further, so they revert to the basic standard, which says: "When X occurs, always do Y, and never do Z" Likewise, when the medical community discovers that Y is actually harmful under some circumstances, there are a crowd of non-lawyers who argue that, for legal reasons, people must continue following the harmful guideline.

While it is entirely reasonable to follow guidelines and standards in most situations, non-standard situations frequently present themselves. A thorough command of the underlying principles will help you provide better treatment, as will an understanding of why guidelines were put in place in the first place. Hopefully, this page will help you understand medical literature and decision-making better.

Not All Evidence (is created equal)

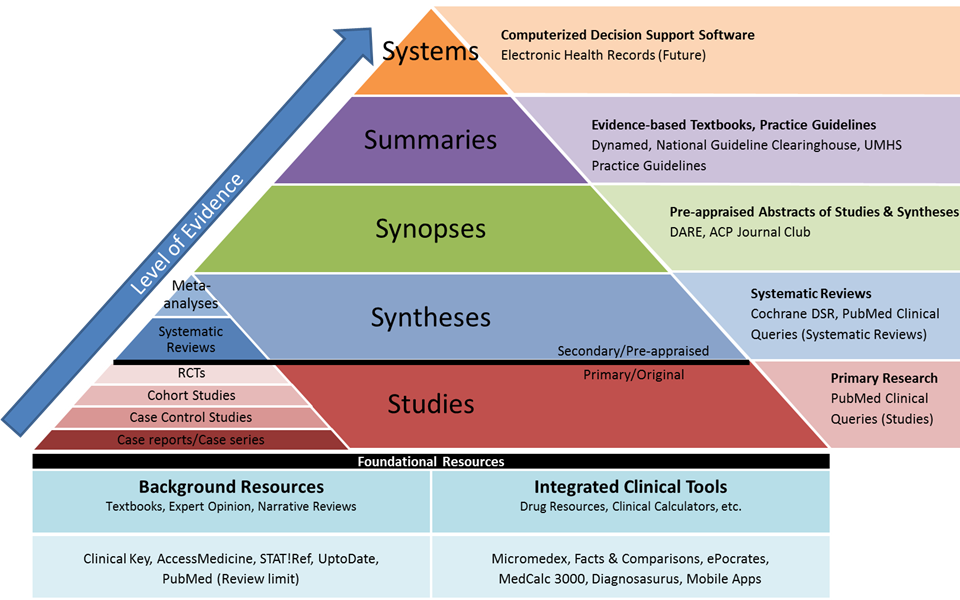

There are a couple slightly-different graphics on the Evidence Pyramid, but I like this one:

At the base of the pyramid are individual studies, which may or may not be valid, interesting, or reproducable. We see these in news headlines: "Harvard study shows blinking lights might cure cancer in rats". This is neat, and they might very well be onto something, but (in another version of the Evidence Pyramid), animal studies are pretty low on the "correlates to success in humans" scale.

Now, after a couple of different centers have reproduced Harvard's results, and studies are done of those studies, we might be able to reason about the effectiveness of blinking lights against cancer (in rats). Meta-analyses and systemic reviews are pretty solid sources of evidence, and if you're new to a topic, I recommend starting there. These studies point out failures in the smaller individual studies, look at differences between them, and basically summarize the results.

Even better are synopses, which are kinda like having your doctor friend read the meta-analysis and tell you what they think. It might be a biased or myopic perspective, but likely better than you'd do on your own.

A step above synopses are "Summaries" - e.g., textbooks and practice guidelines, or "synopsis by committee". This will tell you what a group of experts (typically a professional association or other committee) think about the subject. These groups - especially with textbooks - are usually interdisciniplary - i.e., they have a microbiologist, chemist, and physicist review it, too.

This particular graphic includes "Systems (future)", which I assume has something to do with real-time data and stuff. I guess we'll have to wait and see.

Wikipedia uses only secondary sources - i.e., Synopses and Summaries - for a reason. Their reason is that secondary sources capture what experts in the field think about a piece, rather than what some nobody thinks about a scientific study. This is generally a good approach for the novice medic to take, but does not absolve you of the responsibility to understand the primary sources if you're providing advanced care.

The Number Needed to Treat (NNT)

The NNT is a basic measure of how many patients need to be treated with a given treatment before one is helped. Conversely, the Number Needed to Harm (NNH) tells us how many patients we can treat before one is harmed. If a treatment has an NNT of 10 and an NNH of 100, that means we'd need to give it to 10 patients before we see one result, and we can administer it to 100 patients before we'd expect to see one bad outcome. When the NNH is lower than the NNT, it is considered a risky, dangerous, or just plain bad treatment. Low NNTs indicate effective treatments; high NNTs indicate less-successful ones. Low NNHs indicate dangerous treatments; high NNHs indicate less-harmful ones.

A great example of this is Aspirin for Preventing A First Heart Attack or Stroke vs. Aspirin to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Known Heart Disease or Strokes. For patients with known cardiovascular disease, the NNT is 50 and the NNH was 400. If we administer Aspirin to 400 patients, we should expect 8 people to benefit and 1 to be harmed. In patients without cardiovascular disease, the NNT was 333 and NNH was 250. If we gave 400 of them Aspirin, we should expect 1.2 people to benefit and 1.6 to be harmed. Therefore, we can arrive at the widely-published conclusion that aspirin is probably helpful to people with cardiovascular disease and of little benefit (perhaps even harmful) if taken routinely by patients without a cardiovascular risk.

Another set of NNTs worth reviewing are antibiotic use in open fractures, animal bites, and hand lacerations, as well as Tap Water vs. Sterile Saline for Wound Irrigation.